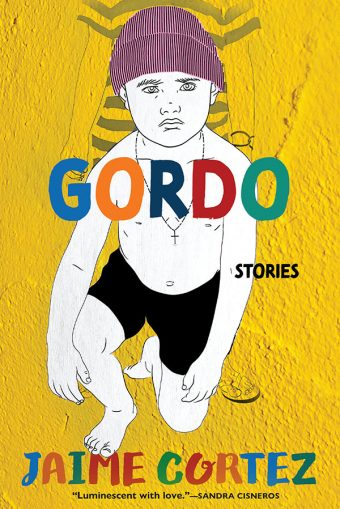

—Jaime Cortez, Gordo: Stories (Grove Atlantic, 2021)

Those with and those without. Money. Strength. Work. Papers. Language. Place. Acceptance. Jaime Cortez’s short story collection, Gordo: Stories, employs the child’s propensity for keen, honest observation to make explicit these implicit hierarchies.

Primarily set in a camp for migrant agricultural workers in California, Gordo explores masculinity in Hispanic cultures. Our main narrator is Gordo, a boy known only by his nickname whose effeminate nature brands him an outsider. From the first story, Gordo feels shame for disappointing his father, Antonio, a traditional Hispanic man. In “El Gordo,” Antonio buys Gordo boxing gear, but Gordo's emphatic interest in the “pretty” sparkly boots elicits a negative reaction. Thus, Gordo learns that his natural inclinations are unacceptable to his father, his peers, and his culture at large.

For Gordo, there are only two options: upset people by behaving naturally or be invisible by keeping to himself and his books. In “Fandango,” Gordo enjoys invisibility on the outskirts of the group of men at the barn party. Only by drinking alcohol, a masculinity-defining behavior in these stories, is he accepted into the circle and by his father, who exclaims “That’s my Gordo!” The only other time we see this pride is when Gordo wins a fight against a neighborhood boy, proving his masculinity through violence. What Antonio doesn’t know is that Gordo’s victory was accidental, and his guilt overpowers any sense of victory he might have felt.

In “The Nasty Book Wars,” Gordo disapproves of Cesar, his older friend and other model of masculinity, hurting Tiny, the youngest of the girls against whom they are warring over a stash of adult magazines. Gordo is torn: “I didn’t really care about the books anymore. It was now a war for the victory of boys or girls— an excruciating binary to a sissy boy like me.” Gordo doesn’t belong to either world, but he understands the dangers of being “different.” We see these dangers later as we follow Raymundo, a gay middleschooler who is bullied and beaten but refuses to fight back.

In these stories, violence amounts to masculinity. Alex, who Gordo thought was a man until he accidentally saw her breasts, is only considered more manly because she abuses her girlfriend, Delia. In Gordo’s words, “[n]obody hassles [his] ma. Except Pa.” Gordo’s mother, Esperanza, declares that Alex is “worse than a man, because she should know better.” This quote expresses a dangerous double standard in Hispanic culture. In “The Pardos,” Nelson Pardo beats his sons whenever they show weakness, and his hatred of women manifests in a schoolwide rumor that he killed his wife. Women, however, are not traditionally violent. Before overhearing a fight between Fat Cookie and her mother, Gordo had “never even heard of a mother and daughter fight.” Upon being violent, Fat Cookie’s mother becomes masculine; Gordo compares her to “a dad coming home on a Saturday after disappearing since Friday.”

While violence persists as a mark of masculinity, silence is expected of women; “Black eyes are top secret…you’re supposed to shut up like nothing happened and swallow the story,” observes Gordo in “Alex.” This silence preserves traditional cultural gender expectations; Hispanic women end up proliferating violence, implicitly teaching their daughters to live with abuse. Which is not to call Hispanic women weak—Esperanza encourages Delia to fight against Alex’s attacks as she did Antonio’s—but not addressing this violence on a larger scale allows such patterns to persist. As a Hispanic woman, I’ve seen many of us have to unlearn behaviors we’ve inherited from the women around us. Upon experiencing life outside of the bubble of our cultures, children living in the diaspora gain the perspective necessary to criticize long-standing cultural dynamics. Maybe this empowers us to challenge the status quo, especially regarding gender-based violence.

Although they don’t speak out, the women in Gordo see. Fat Cookie’s mother accurately predicts that Sylvie, Gordo’s sister, will be desired by men when she’s older. Raymundo’s mother is aware of her son’s homosexuality as a source of harassment and offers him advice. Esperanza defends Gordo against ridicule, calling him her “best helper” in the kitchen. The women in these stories are the backbones of families, the preservers of peace (albeit through at times self-endangering means), the true heads of households. The young girls in the story exhibit this behavior as well. In “The Nasty Book Wars,” the girls refuse to divulge where they hid the magazines: “[W]e’re smarter,” says Sylvie. “We might wait fifty-seven hundred million days before we even look at ‘em.” Their patience, cunning, and, in the case of Fat Cookie, brute strength, overpowers the boys’.

The second half of Gordo presents other facets of Hispanic masculinity. Raymundo becomes a confident artist proud of his town. Shy Boy Pardo, a quiet, homesick artist hidden behind a “cholo” exterior, loses his life to violence, a victim to the demands of masculinity. Even the men’s tough sadness in “Fandango” is unpacked. “I finally understand why the drunk guys scream like women when this song comes on,” Gordo reflects in “Ofelia’s Last Ride.” “It feels like you’ll never stop being sad, never stop wishing you weren’t a loser, but you are. You lose things. You lose people and you can’t get them back.”

Thus, a simple similarity between men and women arises— Delia’s desire to return to El Salvador. Juan Diego’s violent grief over an inexpressible loss. Gordo’s solace in invisibility—we all long for something. I’d like to think this conclusion brings Gordo peace. The worlds of men and women aren’t as different as they appear, so perhaps he can find comfort in the space between.

If you enjoy(ed) the exploration of nontraditional masculinity and the first-generation experience in Gordo, I recommend Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous.

Thanks to Grove Atlantic for providing a review copy.

Brittany Torres Rivera is a Puerto Rican writer whose work deals with culture, family, and (un)belonging. She has a BA in English with a concentration in Creative Writing from Florida International University. She is based in Orlando, FL.

No comments:

Post a Comment