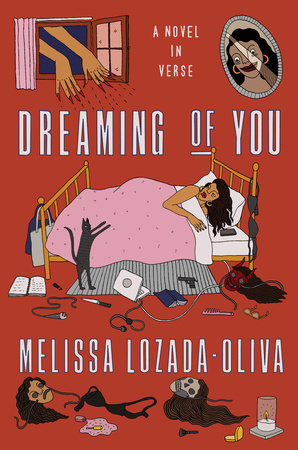

Photo credit: Penguin Random House via https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/675770/dreaming-of-you-by-melissa-lozada-oliva/

“she was a girl who / smelled good and therefore made me / feel like I stunk, but I think I loved that.”

—Melissa Lozada-Oliva, Dreaming of You (Astra House, 2021)

Melissa Lozada-Oliva’s Dreaming of You is a story of expectations and fragmentation. Through characters that represent facets of our narrator’s identity, this novel in verse asks us to reconsider what it means to be an artist, a Latina, a woman, a person.

In my experience, Latinx artists, though drawn to pursue their passions, experience anxiety about doing so as a career. An inherited drive toward financial stability, perhaps something our parents or grandparents were unable to achieve, makes dedication to the arts almost unjustifiable. Add in parental pressure, like her father encouraging her to study medicine, and it’s possible that the narrator in Dreaming, identified as “Melissa,” feels such shame about her profession as a result of a cultural expectation to do something else, something more lucrative or less abstract.

Melissa’s mother expects a different kind of commitment from her. In “March 31, 1995,” Melissa cries to get her father through customs. She claims that, at three years old, she had agency over her actions, but it’s made clear that her mother implored her to make the sacrifice for her family. In “In Which I Answer All of the Questions from My Imaginary and Very Important Interview of the Future,” Melissa’s performance is ignored and she’s forced to sit by her mother. The mother guides the daughter’s life, a common dynamic in patriarchal cultures that keeps Melissa connected, and perhaps subservient, to the family. Abraham Quintanilla, a symbol of patriarchy, promotes this idea in “Dear Ms. Melissa Lozada-Oliva”: “Your parents have worked hard!!!! You should be nicer to your parents!!!”

These expectations create the Selena Quintanilla-shaped hole into which Melissa struggles to fit. Selena was a financially-successful artist and she was close to her family, as chronicled by a biopic and a Netflix series. Selena, then, becomes a benchmark for Latinidad.

In “I Made You a Playlist to Get the Real You Back Even Though Real You Doesn’t Listen to Lyrics,” Melissa and her sister “say [they] hate / country songs to separate [themselves] from whiteness / but what’s the difference between a country / song and a ranchera, anyway?” This strained relationship with cultural identity is explored in “Killing Time at Karaoke” and “The Future is Lodged Inside of the Female,” which contain exasperated comments about Latinx oppression. “The novel is…[an] unraveling of identity…[identity] can sometimes keep us from making progress or helping others,” said Lozada-Oliva. Thus, Selena Quintanilla in this story is not just an archetypal Latina; an intersectional approach reveals her to be a symbol of femininity.

Selena laughs even when men aren’t funny. She is bubbly. She is forever young. “My mom always says that Selena got killed because she was ‘too nice,’” said Lozada-Oliva. “[S]he was trusting and vulnerable...that’s a gift that we’re told to shed away...to protect ourselves.” With her femininity, Selena overshadows Melissa, making her invisible in Part II. Selena is juxtaposed against Yolanda Saldivar, her real-life murderer and a manifestation of the jealousy and bitterness that denote the other extreme of womanhood as perceived by others. Beyond that, Yolanda is much older than Selena. “As a CULTURE,” said Lozada-Oliva, “we just don’t know what to do with [women] when they [age].” In real life, Yolanda’s crime confirms societal expectations for women that aren’t traditionally feminine: they are evil, untrustworthy villains. Thus, the interplay between gender and violence becomes a focal point of Dreaming.

Part I highlights the widespread-to-the-point-of-mundanity violence against women by men. The idea that men are violent is thus established and later challenged by the violence of the feminine symbols. In “Yolanda Leaves a Note,” Yolanda plans to kill Selena to survive; the Selena-shaped hole has taken over her life as it has our narrator’s. “I think [Yolanda’s] saying, we all have holes we need to fit through... this is how I am choosing to get through,” said Lozada-Oliva. She also shared her friend’s thought: “when violence is necessary, why not be able to use it?” The urge to remove that which challenges us is universal. However, while viewed as an indication of an honorable competitive spirit in men, in women, it is discouraged, dismissed as cattiness. As Lozada-Oliva put it, “these women are punished for very normal, human attributes in a way then [sic] men won’t be.”

In the climax, Melissa kills Selena, the symbol of her femininity, to save the man she loves. Thus, Dreaming challenges readers’ conceptions of men and masculinity: “...maybe there’s a way to love men without being oppressed by patriarchy...masculinity, it's actually beautiful,” said Lozada-Oliva. These ideas elicited a conversation I’ve been having with my coworker, a Brazilian woman twice my age, who believes her masculinity has kept her from finding a relationship. This has made me consider my own masculinity, beginning with how I eat; hunched over my plate, I add a second bite before I’ve swallowed the first. I’m not sure what to make of her ideas. Is it okay to change to make men comfortable? When Melissa kills her femininity, is the resulting lack of it what keeps her and her love apart? Maybe violence is agency. Maybe Melissa’s agency sets her free. Maybe the cost of that freedom is love.

Dreaming of You is an excavation of the self. Through fragmentation, Melissa deconstructs her jealousy, her anger, her joy, her love, and explores how they contribute to her whole. In this way, Dreaming is a coming-of-age novel. ‘“[T]owards the end,'' Lozada-Oliva said, “the narrator starts to feel more comfortable and empowered, because she’s let the hang-ups of her youth go, or simply accepted them.” Does time heal all? Can resurrecting the past help you move forward? Are these mutually exclusive? Perhaps finding these answers is part of growing up.

If you enjoy(ed) the intersectional protagonist and exploration of identity in Dreaming, I recommend Paule Marshall’s Brown Girl, Brownstones.

Thank you to Melissa Lozada-Oliva for the interview and to Tiffany Gonzalez and Astra House for the review copy and ongoing support.

Brittany Torres Rivera is a Puerto Rican writer whose work deals with culture, family, and (un)belonging. She has a BA in English with a concentration in Creative Writing from Florida International University. She is based in Orlando, FL.

No comments:

Post a Comment