Anderson Center

What follows is an interview Letras Latinas Blog conducted with Joseph Rios, the 2015 recipient of the John K. Walsh Residency Fellowship (formerly the Letras Latinas Residency Fellowship). The accompanying photographs were provided by Joseph Rios.

***

If memory serves me,

this was your first experience with an extended "writing residency"

of these characteristics. Would you share with our readers what this was like,

being a first timer. Did you develop a work routine while at the Anderson Center?

If so, could you describe a typical day.

You're right, this was my first residency. I have Letras Latinas

to thank for the opportunity. I've been a part of week-long workshops in the

past, but nothing with this much time, this must freedom and, in turn, this much

intensity. For the readers that are unfamiliar with the fellowship, the

Anderson Center sits on the outskirts of Red Wing, Minnesota, a town of ten or

so thousand people. It's small; it's rural. Their main industry, besides the

eponymous boot plant, is corn. Maybe you can imagine the fields upon fields of

corn stalk standing over seven feet tall waving in unison at the sunset. This

image and many others still ring fresh in my mind. But as I was saying, the

town is small, but surrounded by natural beauty. Red Wing hugs up against the

Mississippi river and the state of Wisconsin. Time slows down there, days

lengthen from one to the next. I learned quickly that my greatest ally and my

greatest adversary were the same: time. I couldn't help but think of that episode

of the Twilight Zone with Burgess Meredith. You know the one. He survives some

sort of the air raid while sleeping in a bank vault and when he emerges, he

realizes he has all the time in the world to read. I won't spoil the ending,

but it was something like that. I'm so used to squeezing in an hour or two into

a day to devote to my work. Early on in that first week, I caught myself

feeling rather accomplished after being able to make, what I thought were,

great strides on my manuscript. Then I realized it was only day three and it

wasn't even lunch time. I had a long way to go. I think the word for it is:

stamina. Like a runner, I had been trained to run sprints. And this residency

was about long distance. My lungs weren't prepared for it. It should be

said that I was the youngest resident in

the house, too. These are related, I assure you. I benefited immensely from the

examples of the other artists, twenty and thirty years my senior. They modeled

the sort of work ethic it takes to fully commit one's self to the craft, to

make art their livelihood. I could see that they had honed and developed their

practice over years and years. They were long distance runners.

In the morning, I woke up at a reasonable hour and usually

wandered down to the living room or to one of the few libraries and sitting

rooms in the house. I carried around three or four books with me everywhere I

went. I spent the first few hours each day reading what I found on the shelves.

I paid special attention to one's the director, Robert Hedin, had bookmarked

with slips of scrap paper. I treated these markers as homework assignments.

This led me to books of poetry by former residents, short story collections, hand pressed

chapbooks, essays on art, and biographies of poets, scientists, and movie

stars. Like a good poet, I carried around a note pad. As you can imagine, poems

came out here and there. Old memories sprang up. Starts and finishes of poems

arose from that stillness, from that dedicated meditation on the word. They

were sputters, mostly. The fragmented lines were the kind of engine noise and

exhaust you hear on a cold morning when you first try to start up a lawn mower.

I got warmed up, though, to be sure. I found a rhythm to really get into some

work. I was able to really read, really revise. I could really see my

manuscript as a body and see its many faults. It felt good. The feeling was

familiar. When you train for long distance runs, there is a point around mile

six or seven when the body settles down into another gear and each step comes

with less strain. Breathing normalizes, arms and feet sync up. You even start

to feel pleasure from the work. I felt that. I stopped trying to hurry through

the writing. I slowed down. I took each moment as it came and I tried to commit

everything I saw and read to memory. Small things, like the mosquito netted

porch with a view of the green house and the west lawn. I would sit out there

before noon and I'd see Robert march past the greenhouse and over to the turtle

pool. He'd take a puff on the cigarette he kept cupped in his hand and peer

into the water at one of the three turtles inside. It was like clockwork. Just

about everyday he did this. And he'd always look over and wave and then march

back up to the office. I hold tight to these images, these memories. I wrote

them down. All in all, I just kept working, writing and revising. And,

honestly, that's all that was expected of me. That was one of the more unique

elements of my experience there at the Anderson Center. When I woke up, when I brushed

my teeth, when I made lunch or went to the supermarket, I was a poet. Nothing

more, nothing less. I held no other title. I wasn't anyone's employee. I had no

obligations placed upon me other than to create. In Red Wing, I was just a

poet. I was there to read and write poems for thirty one days. I had no other

responsibilities, nothing holding me back but myself. And when I was able to embrace that, the work

came.

Joseph Rios

My understanding is

that you were working on a first book manuscript. What project did you set for

yourself, and how did things go. What kind of progress did you make? What do

you anticipate still needing to do to shape this project to a point where you

might send it out?

I've been working on the same manuscript for a handful of years

now. I've submitted it to different places. It was a finalist for a prize once,

but even that seems like a lifetime ago. Lifetime for the manuscript, I mean.

At different points, I thought I had something near or close to done. The weeks

at the Anderson Center really made me see otherwise.

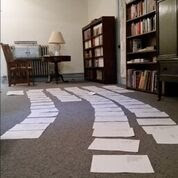

I did what most poets do during their residencies. I printed and

laid my manuscript out on the floor. Of course, I took the ubiquitous photo of

the process and posted it on my instagram (see @josefobear). But really, I did

do that. I went up to the attic and spent a few days just reading and

mercilessly tearing through that thing. I made sharp revisions, cold blooded

expulsions, and was able to come up with some fruitful re-writes. Those

sessions allowed me to see the landscape of the book. It was like that short

trip some of us took up to the bluff that overlooks Red Wing. From that height,

we could see all of downtown, the Mississippi, and off into the trailer park

bar on the Wisconsin side, the strip club, and the firework stand. If the day

was clear, we could almost see the Anderson Center, too. It was something like

that. I could see where things were developed and I could also see the gaps in

the book. You know, like Rocky says, “You got gaps, I got gaps. Together, we fill

gaps.” I could see where there were poems that still needed to be written. I

could see the holes. Many readers of this blog are probably familiar with this

process. It's a first book poet's problem, I think. We're so fixated on our

debut and we don't realize that as we plow on without that first satisfaction,

we might actually end up with more than one project on our hands. Letting go is

tough as all hell. That's what I realized looking through the thing. Some of

the newer stuff I've been writing doesn't necessarily match what was going on

in those earlier poems. And that was my greatest obstacle: I wanted to revise

and rewrite while maintaining some sort of respect for that voice that wrote

those early poems, honor the individual poem without making it something

entirely new simply because I was frustrated with it or felt like this me knows

better than the old me. Does that make sense? Basically. I went in wanting to

work on the last section of the manuscript. When I was done, I had crumpled and

tossed out a lot of stuff, things I'd grown tired of reading, tired of looking

at. I sat down with poems I did like and really started working my hands into

them. They got better, I think. I moved things around. I was able to see how

each section differed from the other, how they developed and worked along side

each other. I've said this already, but

it felt good. I genuinely took joy from it. Tearing apart the thing was the

good kind of painful. As for next steps,

I just have to keep writing. I have to fill those gaps still staring me in

face. And like my self-proclaimed mentor Javier Huerta says, I gotta think

about the layering of the piece. So, yeah, some of that makes more sense now.

As they say, the real work begins now that the residency is over.

It also sounded like

your experience at Red Dragonfly Press, the in-house press at the Anderson

Center, also provided a meaningful experience for you. Could you share with our

readers what that was?

I grew up in machine shops and garages. My grandfather, my uncle,

and my father taught me how to use tools, how to make and fix most things.

There is a logic to it that's been welded to my brain, it's etched on the

muscles of my arms and to my fingers. It's a set of rules and standards that

keep the machines running and keep all my limbs and digits intact. Even though

these experiences find their way into my poems, I've never seen the skillset as

transferable or translatable to the actual creating of poetry. I thought, in

the most basic sense, there was as much separating poetry and the machine shop

as there was separating the figurative and the real.

When I walked into Red Dragonfly, I was taken most by the smell

of the presses. With my eyes closed, I could have easily been in my

grandfather's garage or my uncle's airplane shop in West Fresno. It was the

smell of old lead, aged iron, small motor exhaust, and grease. The tools in

that place were of my grandfather's era. They were forged around the same time

as his. When I felt them and held them in my hands, I knew. Tom Virgin, a

master printmaker and fellow resident, encouraged me to make a print. I

hesitated at first. I wanted to set a poem that had some ties to the Center, so

I wrote one for Robert in honor of his retirement. I called it, well,

“Retirement.” It took me about two days to set that son of a gun, on account of

my big iris root fingers. I may be a

poet, but I accept that my hands are meant for more “smash like hell ” than the

delicate placing of small lead type. It's a monk's work. I spilled the lines

into piles of alphabet soup more than once, but I got the hang of it. The

principles of making and using the tools and machines came like second nature.

When my hands got on the press, when I switched it on, and the sprockets began

to crank, I knew. For the first time, the machine shop education – all that

training from childhood, making mistakes, breaking things, getting yelled at by

my uncle, losing my grandpa's tools, falling from ladders, getting zapped by

wall sockets, soaking under sinks in garbage water, cutting my knuckles while

turning wrenches – all that was being put to use to turn out works of poetry.

My grandfather, my uncle, and I don't have long conversations about poetry, but

I know they would have felt at home in that shop. Things would have made sense

to them. Half a day on the press and they'd be master printers. I really

believe that. I felt more connected to the word during those days I sweated in

that shop, I felt more connected to the knowledge that had been passed on to me

all those years ago. I felt like I was inhabiting the poem, setting each letter

like a brick in the wall, repeating the lines to myself over and over like

meditation. I could also hear my early mentors' voices tell me to pay more

attention here or be careful with that there, watch out for yadda yadda, duck

your head cabezon or it'll get bigger, look around, be mindful of your

surroundings, listen to what's happening on the other side of the shop, know

the next move before you get there, watch where you're stepping, don't force it

or you'll break it, and on and on. Things really connected in that shop. A

bridge was made there between two worlds of experience. I felt like I was in

communion with my fathers and we all were in communion with the poem.

Finally, as someone

who now has a first extended writing residency under your belt, so to speak,

what advice would you give to someone who was about to have the same

experience, for the first time.

First, thank your gods for the time. That's what we poets and artists are

after, right? More time? Honestly, I didn't seek out much guidance before

heading to Minnesota. And I'm not really one for giving advice either. I would

suggest going into the place blind.

Discover the place brand new. I had to explore and find my own space in Red

Wing. I learned more about my own practice that way. I feel like I understand a

bit more about how, when, and where I work best. It was hard. I learned to take

it all day by day, morning, afternoon, night. I'd devote chunks of time to

different things. I mean, it's all there for you. You are given whole days and

weeks. And unless you are one of the few that can make a living just on your

writing, you know how rare of an experience this is. If I could say anything, I

would suggest being pointed with the days, have work to do. You won't always

feel like doing it. That's when I'd take a walk or find something to read. I'd

make a quesadilla or go peek in on one the other residents. It's good to get

outside. There in Red Wing we were surrounded by majestic greenery, rivers, and

wildlife. We would take bike rides in the afternoon before dinner. It was good

to go outdoors, to move the body, to sweat, to breathe heavily. During those

hour long rides, we got to know each other. We got to talk about our work and our

lives back home. We were all from different parts of the globe. All artists,

all trying to make the most of the time. I cherish the friendships I made at

the Anderson Center. I know I'll see my fellow residents again. You know, all

this talk about the residency has me feeling a little misty. I really loved my

time out there. I met some beautiful people and I got going on a lot of work.

My only hope is that other writers have the opportunity to experience something

similar, abundantly and often. c/s

No comments:

Post a Comment