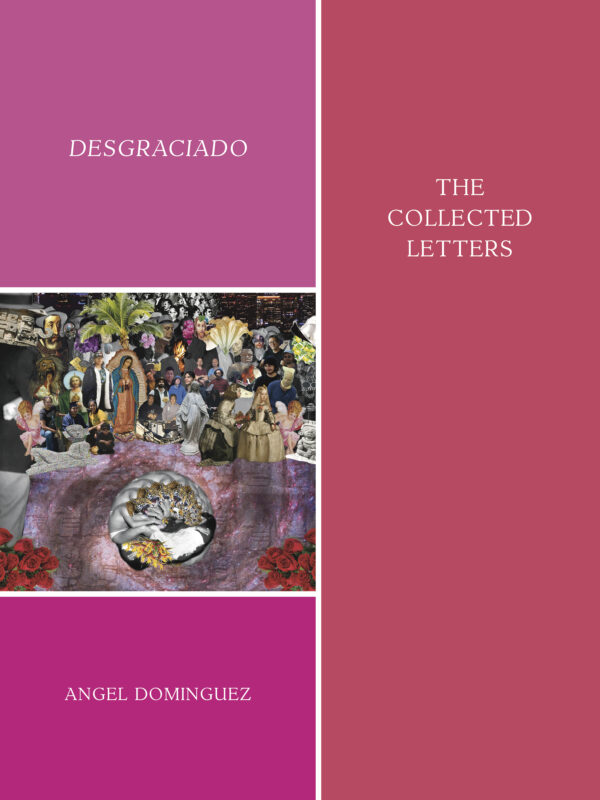

Photo Credit: Nightboat Books via https://nightboat.org/book/desgraciado/

“Stripped of its mother tongue, my body is compliant. My body searches for its organs in the rubble of the oppressor. My body sifts through language patching shards together until there is an echo of…the mother song.”

—Angel Dominguez, Desgraciado: (the collected letters) (Nightboat Books, 2022)

In Desgraciado: (the collected letters), Angel Dominguez confronts the lasting physical, historical, and sociopolitical violence of colonization in a series of letters to Spanish colonizer, Diego de Landa.

The letters in Desgraciado mourn the loss of the Mayan language and people at the hands of Diego. Although on the surface Diego is simply a villain, Dominguez ventures to see this symbol of colonization as an ancestor, paternal figure, lover, and oppressor. Dominguez told me about their relationship with Diego: “I only wrote to him…things I couldn't talk about with anybody…I started to fall in love.” And, indeed, the letters follow the ebbs and flows of a relationship complicated by centuries of violent history; love becomes understanding becomes indifference and then hatred. But beyong unpacking their feelings toward him, the narrator’s letters reveal their desire to share the truth of Diego’s role in the Mayan genocide. Rather than retell the colonizer’s version, Dominguez challenges the notion that history is in the past: “[history] is this living thing that we engage with.” The violence of the genocide is detailed in the letters, a violence, Dominguez argues, that should not be forgotten. “My grandmother remembers,” reads one of the letters. “The temples may be ruins but we…We are alive.” This collection does not seek to resolve or ‘forgive and forget’ the past, calling instead for descendants of oppression to expose and retaliate against systems that perpetuate that oppression however they can. For the narrator, that is through writing: “Language is a weapon…Sometimes, healing is not what we need.”

Dominguez called writing Desgraciado a process of “expel[ling] the internalized traumas of colonization and systemic racism in America.” Lines like “[t]he cold cowardly whiteness of the world hopes we’ll die, or forget our color” criticize the use of language to promote globalism. Rather than prioritize the preservation of histories, cultures, and distinct experiences, globalism strives to assimilate them into an amorphous collection of identities in what Dominguez calls a “linguistic flattening” that favors whiteness. Thus, Desgraciado addresses not only the theft of language as in the attempted decimation of the Maya, but also the use of language as a weapon of colonization and white supremacy. Inextricable from white supremacy in the text is capitalism, as the narrator, who struggles with debt and (un)employment, writes about how capitalism (and “amerikkka”) is fundamentally racist: “empire can say…The brown body died in poverty because [it] did not try hard enough.” This is exacerbated by the control capitalism and white supremacy have over education; one of the letters reads “[my own people have] equated Westernized intelligence with whiteness.” This reminded me of an exchange I’d witnessed in high school. We were discussing what it meant to “sound white,” something that had been said about a Black student, when a white student said that speaking like a white person meant speaking “properly.” The statement caused an uproar in the class, but the fact that this student asserted this idea so comfortably speaks to the far-reaching impacts of colonization, and it serves as yet another instance of language being manipulated to benefit the oppressor.

As I read this collection, I couldn’t help but relate some of the narrator’s sentiments about unbelonging to the literature of the Latinx diaspora: the desire to learn the mother tongue, the separation from homeland, the claiming of a culture only partly understood. When I mentioned this to Dominguez, they brought up gentrification, displacement, and rootlessness, saying “our histories are taken from us forcibly.” Like Kyle Carrero Lopez’s Muscle Memory, Desgraciado points out that Latinidad does not apply evenly to all. “I’m not Hispanic, not Indigenous, nor Xicanx/Latinx,” writes the narrator, and, in another letter, “I honestly don’t know what [‘us’] means anymore.” Dominguez said “Latinidad is dead” because the language surrounding it (words like “us” and “we”) implies community where it doesn’t necessarily exist. Like Muscle Memory, We Are Owed., and other books covered in this column, Desgraciado seeks to highlight the vast differences in privilege and opportunity that exist for Latinxs of different cultures and races. Although it is a book of the diaspora, Desgraciado is a work for displaced people, regardless of identification. In reading this collection, I have been forced to reckon with difficult questions surrounding the way I construct my identity: Is it around the oppressor? Does taking pride in a (violent, colonial) shared history make us complicit in the continued oppression of Black and Brown people? I don’t have the answers. But the book’s narrator dreams of a world in which oppressed peoples can destroy and thrive without colonial empires, “living long enough to see one’s enemies fall.” Perhaps such a goal is a worthier cause to rally around.

Toward the end of our interview, Dominguez called Desgraciado “a struggle.” And the final letter of the collection confirms this: there is no “healing narrative,” no happy ending, no conquering the conqueror. There is just an eternal conversation between Diego and the narrator. The narrator’s mission— re-revising history, portraying Diego as he is, setting the ledger straight— goes beyond history. It's something that affects one’s own perception of self. Who am I to the rest of the world? Who am I to myself? When I close my eyes, or when I write a letter to the person that haunts me, how do I relate to this person? It comes down to history, to the un-flattening of language, to the active reversal, or, as Dominguez writes, “revenge,” against forces of oppression that seek to deny truth, lived experiences, and identities, past, present, and to come.

Thank you to Angel Dominguez for the Zoom interview and to Nightboat Books for the review copy.

Click here to read Angel Dominguez's essay on the death of Latinidad.

No comments:

Post a Comment