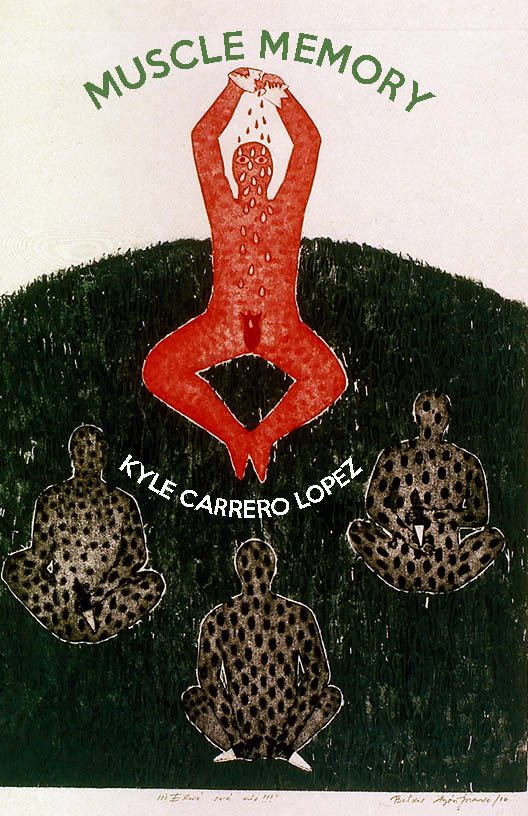

—Kyle Carrero Lopez, Muscle Memory (PANK, 2021)

Kyle Carrero Lopez’s debut chapbook Muscle Memory challenges social, economic, and historical authority, combining compelling sonics with diverse poetic forms to discuss Blackness, capitalism, and the implications of historical oppression on culture.

In “Black Erasure,” the first poem of the collection, Carrero Lopez replaces the word “Black” with the letters “[POC],” a device as visual as it is metaphorical that demonstrates the minimization of the Black experience in the U.S.: “[POC] Lives Matter to the public / for about a week at a time.” Replacing Blackness with a vague cloud of identities refutes the shared history of Black people in the Americas. The phrase “POC” also conflates the Black experience with that of Latinxs in the diaspora who may harbor internalized anti-Blackness. “The conception of Latinidad…has necessitated…a sort of homogenization,” said Carrero Lopez when we spoke. “We're white, Black, Indigenous…Many people still are uncomfortable with the idea that there’s a difference.” This idea is espoused by lines such as the epitaph and in “From an Agnostic,” which explains the importance of the Afro-diasporic religion Santería as a unifying factor for Afro-Latinxs using parentheticals: “(Because Yemayá’s portrait in any home / brings me home).” As a white Latina, I was taught that Santería was mystical and antithetical to the Christian beliefs that saturated my extended family. However, Muscle Memory is part of a growing collection of Afro-Latinx books that challenge these cultural notions. As Carrero Lopez said, “there isn’t Latin American culture without Blackness.”

One way this cultural interplay arises in these poems is through the discussion of labels. “Mi Gente Estadounidense” reads: “‘Latino’ is a vintage, oversized sweater—not for everyone.” This line shows the over-simplifying nature of certain labels: “I’m not Mexican, but whatever, aren’t we all, here?” This ties back to the use of POC to lump together a swath of disparate experiences. In “(SLANG)UAGE,” hyphenation (as in “Afro-Latinx”) is a possible solution to the muddling of individuality that results from the term POC, intentionally acknowledging the two cultures it conjoins. But the hyphen can also “rotate / to a wall,” appearing to some as an intra-cultural division. “[People] who are very strongly American don't even want to hear about your African-Americanness,” said Carrero Lopez. However, hyphenation can help people recognize the consequences of historical subjugation and challenge the prevailing discourse about them, something that several authors featured in Wild Tongues Can’t Be Tamed touch upon as well. “In order to build new things,” said Carrero Lopez, “you have to understand how the old things worked.” Muscle Memory identifies problems with these “old things” by illustrating the carceral state.

“There's muscle memory involved in in the perpetuation of slavery,” said Carrero Lopez. “When you've had a particular system working in a particular way for such a long time, you have to abolish the system entirely.” The poem “After Abolition” presents similarities between slavery and the prison industrial complex, making the case that the U.S. police state is just another iteration of slavery. This idea is reinforced in the poem “Petty,” where the speaker jumps a train turnstile and is confronted by a man “who kneel[s] to a state’s boots for licks.” This kneeling symbolizes the repeated empowering and subjugation of the same groups; Carrero Lopez described how New York police target subway stations near Black and Latinx neighborhoods when “there's actual white collar crime being committed constantly.” This selective misuse of authority echoes the original purpose of police: slave patrol. But targeted policing is not the only evidence of slavery discussed in this collection; In “Modern Fiction,” an English professor teaching at a university that used to be a plantation reads the n-word and students glorify a slave owner while the speaker is the victim of a racially-motivated verbal assault (“what strikes breaks skin, soars past bone, / through each lobe and out). These poems explore repeated patterns of abuse, which will be replicated unless the existing system is replaced. Muscle Memory, then, is a series of tableaus that challenge readers to question “whether or not we want to keep [what we've been handed],” as Carrero Lopez said.

Racism in the U.S. is not only historical, but also economic. Capitalism, Carrero Lopez says, is “inextricable from how [he] understand[s] racism.” In “Note to Lightness,” the speaker admits the advantages that having light skin granted him, both in the workforce and as a man; “If manhood gave me a stage, / you got me the mic.” This quote shows that, while being a male can be an economic privilege, racism negates this privilege to Black men. His lighter skin allows the speaker to reclaim some of this advantage, although it’s still not enough in the poem “Monday,” where “some white guy / on [his] team, same experience level, got hired / a whole title ahead.” Muscle Memory also touches on the commodification of Black bodies in poems like “Beauty Examined,” which asserts that, when disenfranchised, people become symbols and are capitalized upon by corporations to sell items like the Black excellence t-shirt worn by a white man in “Black capitalist wet dream.” Carrero Lopez refers to this “cooptation” of Black culture and expression as “the story of Blackness.”

“These are not hypothetical questions,” Carrero Lopez told me. “[A poem can] ask people to decide for themselves what [they’re] getting from [it].” And Muscle Memory succeeds in this respect, saying it like it is when necessary while still granting readers ample room to reinterpret poems with each new reading. Featuring playful rhymes and haunting images, these poems challenge readers to question what they’ve been taught, lest systems of oppression return under “with new names.”

Thanks to PANK for the review copy and to Kyle Carrero Lopez for the Zoom interview!

No comments:

Post a Comment