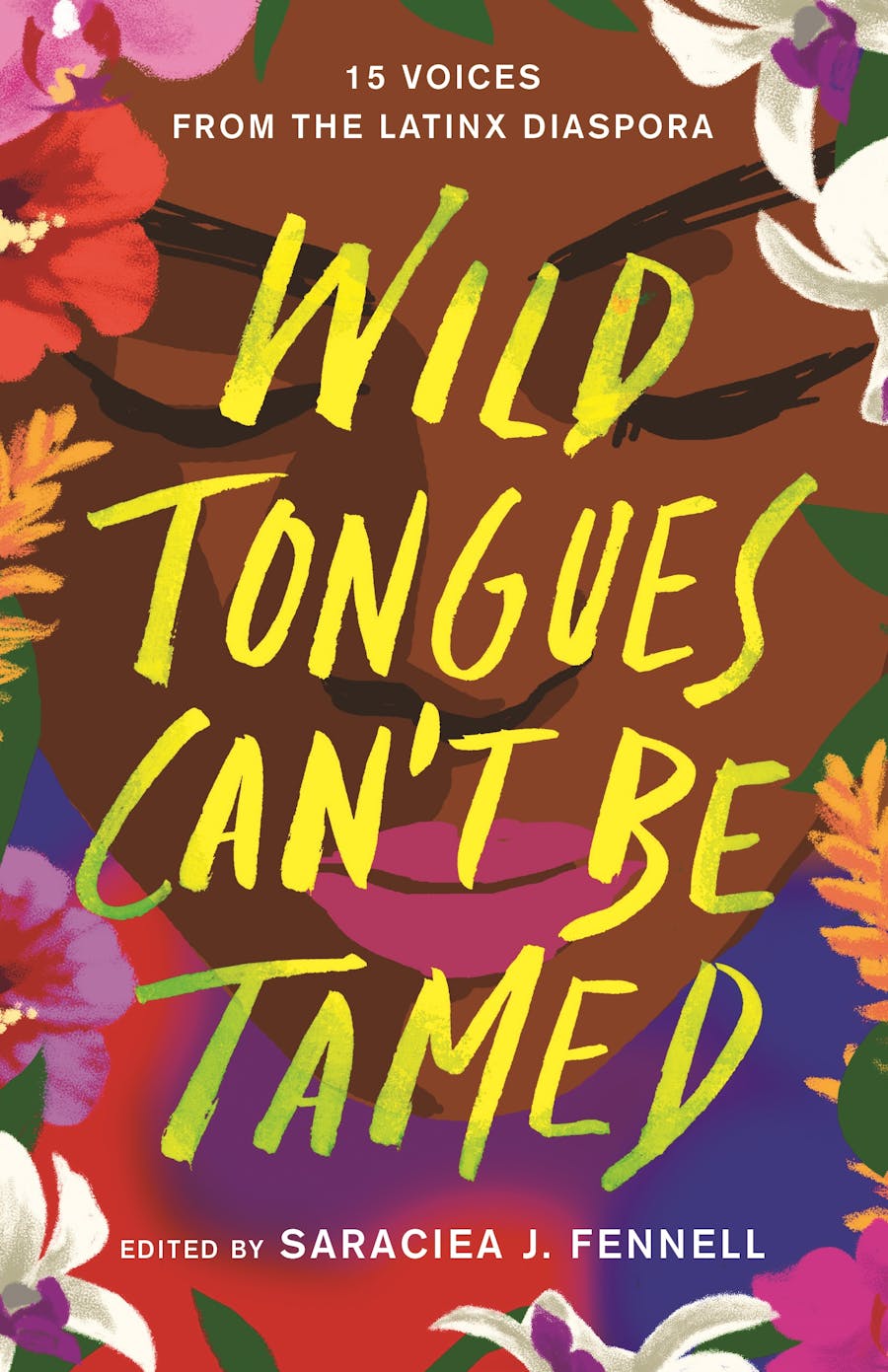

Photo credit: Macmillan Publishers via https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250763426/wild-tongues-cant-be-tamed

—Cristina Arreola, “The Land, the Ghosts, and Me”

from Wild Tongues Can’t Be Tamed, edited by Saraciea J. Fennell (Flatiron Books, 2021)

In Wild Tongues Can’t Be Tamed, authors from various Latinx cultures share their diasporic experiences. Edited by Saraciea J. Fennell, a Black Honduran Indigenous American, this anthology centers underrepresented Latinx voices. These pieces explore hyphenated identity and intersectionality to broaden the canon of Latinidad.

Most authors in this collection express a longing for language. Mark Oshiro’s “Eres Un Pocho'' tells of a man trying to reclaim his Mexican heritage by learning Spanish, and Natasha Diaz references “a language” she knows “only in lullabies.” This lack leaves some feeling unable to claim their culture. It’s something I’ve heard before; my classmate once said she wasn’t a “real Puertorican'' because she didn’t speak Spanish. Not speaking the mother tongue creates a painful reality for second-generation children hungry to connect with their heritage, but it also highlights linguistic discrimination in the U.S. Sometimes, as in the case of Zakiya N. Jamal, the lack of language comes from parents’ fear that their children wouldn’t assimilate, that their opportunities would be limited, that they wouldn’t be respected if they spoke another language. This severed connection, then, speaks to linguistic privilege, as immigrant parents might feel forced to choose between their children’s belonging and their success.

For Janel Martinez, writer of “Abuela’s Greatest Gift,” Spanish is one of two missing mother tongues. The other is Garifuna, spoken by the Garinagu, an Afro-Indigenous community living throughout Central America. By including this and other essays in Wild Tongues, Fennell accomplishes a specific goal. “When we look at the Latinx canon,” Fennell said, “it lacks several experiences that Wild Tongues centers, like Black, queer, and Indigenous experiences.” As a white Latina, this anthology put me face-to-face with ugly truths about the culture to which I cling so tightly. “Not only does Latinidad erase Blackness and Indigeneity,” writes Martinez, “but it also relies on one’s proximity to whiteness, as well as how much privilege one has based on gender… language spoken, and mobility, among other things.” Other writers reflect upon the same sentiments.

One recurring idea is the prevalence of mental health issues, especially for Latinas. Elizabeth Acevedo writes: “So many young Latinas struggle privately and inwardly with being overwhelmed, depressed, anxious, and those feelings are met with the external expectations of boca cerrada te ves más bonita.” This might be explained by a socioeconomic issue brought up by Lilliam Rivera in “More than Nervios”: “Essos son los blanquitos…seeking medical help for anything dwelling in the mind is really meant only for a privileged few.” Here, whiteness and money are privileges that differentiate Latinx experiences. Rivera mentions needing to “maintain appearances” and the stigma around mental health therapy. These may be intensified for Latinxs striving to present as a “model citizen,” something Naima Coster references in “The Price of Admission.” One cause of stress in the lives of young Latinas may be a sense of displacement, whether due to their spoken language or the language they use to refer to themselves.

For instance, Afro-Latinxs may have a unique linguistic experience from other Latinxs. Jasminne Mendez, a Black Dominican, describes feeling like a “circus sideshow” for speaking Spanish. Many BIPOC authors in Wild Tongues detail a complicated relationship with their hyphenated identity. In her piece, Fennell writes that, upon learning she was part Hispanic, some peers would be “excited” that she wasn’t “just another Black girl.” In “#Julian4spiderman,” Julian Randall writes that half-Black-half-Puertorican Spiderman Miles Morales’s “least believable power” is that he doesn’t feel pressured “to prove his Latinidad.” Wild Tongues expounds on people with hyphenated identities not feeling sufficiently either. Although many U.S.-based Latinxs feel that push-and-pull regardless of race, Wild Tongues highlights the added effect that racism has on this, both in the diaspora and within Latinx cultures. Authors point out the lack of Afro-Latinx representation in popular media, making characters like Miles Morales all the more significant. As Randall writes: “I was born into a country of no rain, so when it drizzles, I see a river; I see my face in every drop.”

As I read this anthology, I was struck by its thematic similarities to last month’s read, Ariana Brown’s We Are Owed., especially regarding the issue of labeling. On the pages of Wild Tongues, authors change, embrace, and reject labels depending on their experiences. Names bear a similar power to labels, as Jamal describes feeling “inauthentic” for having an African name rather than a “Spanish” one. She describes this dual-culturality as “two halves…at war.” I relate to this, although my name (along with my sister Tiffany’s name) is often associated with whiteness (have you seen White Chicks?). My name separates me from my culture, a sensation compounded by my diasporic upbringing. Of a similar experience, Cristina Arreola writes: “I haven’t been steeped in the culture long enough to make me strong with its flavor, but just enough that you couldn’t hide the scent.” I do, however, want to differentiate these experiences, as my discomfort with not being coded as Latina carries the privilege of whiteness and not the burden of racism. However, I think the significance of labeling can be seen in both cases. “[Labeling] is used…to define who we are at that given point/moment,” said Fennell. “[Y]ou can’t really [label] people, especially communities of color because we are always evolving.”

When I started this column, I wanted to view Latinidad from unique perspectives separate from my (very privileged) one. Reading Wild Tongues Can’t Be Tamed, and last month’s We Are Owed., has greatly contributed to this education, and I am excited to see where else these stories take me.

Thank you to Flatiron Books for the review copy and to Saraciea J. Fennell for making time for an interview!

No comments:

Post a Comment